Try your first class free.

If you like it, and we are sure you will, if you continue to train, pay only $99/unlimited classes for 1 month and receive a $150 quaility uniform free. Valid until March 31st 2026.

*New students only

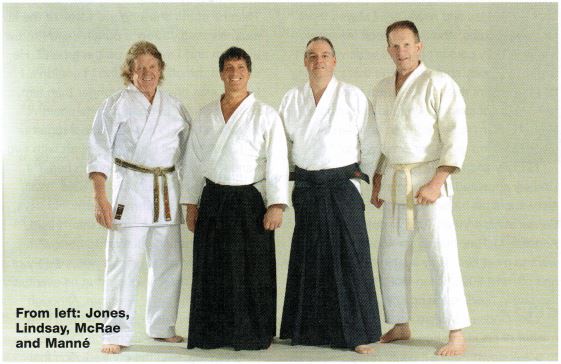

In a quiet backyard dojo in Nunawading, Melbourne, a couple of Australia’s best known martial artists have come to assist their aikido instructor in his first photo shoot for Blitz. They, of course, are old hands. One of the men is kickboxing pioneer, former bouncer and bodyguard, founder of Zen Do Kai karate and all-round hardman, Kyoshi Bob Jones. The other is Kyoshi Billy Manné, a Zen Do Kai karate legend of similar experience and repute. The question is, why are they now here – as students?

All this softness is killing me!” jokes Kyoshi Billy Manné as he shakes the pain from his wrist and rises back to his feet for the umpteenth time this morning. I’ve never been cared to death before!”

Helping him up, his aikido instructor Sensei Malcolm McRae laughs aloud, but Manné is only half joking. The six-foot-five freestyle karate instructor has seen his fair share of hard knocks in over four decades of martial arts training and security work. On this unseasonably cold November day — it’s snowing just a little further afield in Melbourne’s outer east – his body is not enjoying the punishment as it is sent crashing to the mat repeatedly, despite his ability to breakfall.

So what is Manné — 7th Dan Black-belt and holding equal rank with his instructor, friend and head of Bob Jones Martial Arts (BJMA), Kyoshi Bob Jones — doing here? Why is he wearing a white belt around his gi (though McRae is happy for him to wear black), and offering his body up to be buckled, twisted and tossed to the mat?

He, like Jones and several other of his lieutenants in BJMA, have “started again”, in Jones’ words. Though he and Manné are both in their sixties (neither will confirm their age), Jones explains that he had reached a point where he and his fellow seniors in the BJMA, the 7th Dans, knew there were still new territories to chart in their martial arts journey, but weren’t sure where. As ‘The Chief’ of BJMA, which encompasses Zen Do Kai, Jones found himself at a loss as to what advancements they could make to take them to an 8th Dan level and beyond. That was before he met McRae.

“Now Bob’s been introduced to aikido, he sees that there’s something else out there, other than just physical fighting,” says McRae. “He’s never really experienced the way the centre can be taken so softly and was looking for something himself to take him further on in his martial arts.”

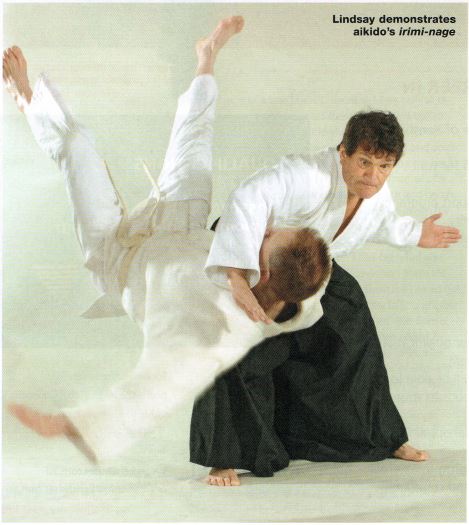

So, here they are with McRae and his right-hand man Sensei Peter Lindsay, a former champion bodybuilder who began studying aikido some 20 years ago under film star and master Steven Seagal.

Lindsay joined McRae in his ki fusion school only a year ago.

When asked what he thinks other martial artists see in his method, McRae offers his own analogy: “It’s like driving a prestige car,” he muses. “People say, Oh, what a waste of money, why do you need a car like that?’ But they’ve never had the opportunity to drive one; they can’t appreciate the feeling. When you have, you understand. In aikido, I’ve driven that prestige car with my Instructor.” It’s a comparison that can certainly be appreciated by Manné, who voices concern for the duco of his Porche, parked in McRae’s driveway, as hail begins spattering through a gap in the dojo’s tin roof. In several years studying aikido with McRae, Manné and Jones have had a chance to do more than kick the tyres – they’ve felt the power behind the purr and know the thrill of superior handling.

When asked what he thinks other martial artists see in his method, McRae offers his own analogy: “It’s like driving a prestige car,” he muses. “People say, Oh, what a waste of money, why do you need a car like that?’ But they’ve never had the opportunity to drive one; they can’t appreciate the feeling. When you have, you understand. In aikido, I’ve driven that prestige car with my Instructor.” It’s a comparison that can certainly be appreciated by Manné, who voices concern for the duco of his Porche, parked in McRae’s driveway, as hail begins spattering through a gap in the dojo’s tin roof. In several years studying aikido with McRae, Manné and Jones have had a chance to do more than kick the tyres – they’ve felt the power behind the purr and know the thrill of superior handling.

Of course, just as no-one wants to buy a car without a test drive, McRae understands that skeptics – and journalists – need solid proof that his aikido, which he describes as ‘ki fusion’, really works. And he doesn’t begrudge them that.

It was around eight years ago that Jones and company got their first demonstration of aikido, when the Victorian head of Zen Do Kai, Steve Nedelkos, organised for about 70 of their members to do a five-hour seminar with Sensei David Brown, McRae’s instructor. A quiet but much-respected senior instructor in the Aiki-Kai aikido organisation, Brown had introduced McRae to aikido after McRae became his apprentice as a watchmaker. Dutifully, McRae was there to play uke (receiver) to his sensei at the seminar. But as it turned out, things changed up.

“David announced that he wasn’t going to teach anybody aikido, he was just going to teach them the relationship between punching and kicking to help in their own style — and I thought, ‘this is going to be good’,” recalls McRae, who audio-taped the event. Brown began by asking Nedelkos and Jones to offer up their best fighter present — “some tall blonde guy, 5th Dan or something” — and Brown politely requested that the karate-ka punch and kick him in whatever way he chose. “[The man] said, ‘Are you sure?’ and David said, ‘Well, I wouldn’t be standing here if I wasn’t sure’ and he let him have it. David just effortlessly decked him and Bob stood up out of the seat and said, ‘Could you do that again?’ Dave said, ‘Yeah certainly’, and proceeded to do it for the rest of the class. So the class, instead of being a workshop, ended up being more of a demonstration.”

In my case, McRae is kind enough to let me experience the prestige ride too — or at least, be run over by it at low speed. If you want to experience it from the driver’s seat, in the comfort of a pair of hakama (the billowing black pants worn over the gi by aikido Black-belts), best get behind the wheel ASAP and prepare to spend a decade or two learning how to handle it. (Although, McRae says he’s able to teach the skill and understanding of ki fusion in less time, and is impressed with the progress the BJC men have been making.)

For now, McRae gives me the standard demonstration of his ability to fuse ki — “just so you don’t walk away thinking, ‘pah! This is crap … these guys are kidding themselves’,” he says, laughing. He asks me to grab his wrist as hard as I can, first with one hand, then with two, and try to stop him from breaking my grip. First he pulls and yanks, demonstrating what happens when he employs muscular strength: it’s two grimacing men in a tug- of -war (he, at over 90kg, is a lot bigger, however, and with the lesser grimace). Then he reverts to using what he calls ‘ki fusion’, and removes his wrist from my hands with such ease I can barely feel it happening. No speed, no yanking, no perceptible strength; I simply can’t hold onto him.

Next, using a traditional aikido demonstration often called ‘the unbendable arm’, he places his wrist across our photographer Charlie’s shoulder and Charlie tries to bend his arm. Then we both try hanging off it, to no avail. Needless to say McRae has little trouble bending my arm. Or doing anything he likes with it, really. I try a bear-hug. Trying to pick him up off the ground is like trying to budge a bulldozer, though I’m not sure that even if I could do that, I’d be able to move this man any more – that is, more than not at all.

Even after first allowing his chosen demo-dummy to assume his strongest stance and carefully apply his grip for maximum purchase, McRae expends no effort, and little visible movement, in putting me, Manné, or his right-hand man Lindsay – who at 92kg outweighs me considerably – on our backs. This is greatly preferable to experiencing his wrist – locks, however, which feel different to any I’ve felt before; softer, a burning sensation through the limb, and a sudden desire to go where he wants me too. I’d rather not escalate the demonstration to punch-defence, lest he find it necessary to raise the pain-delivery ratio in equal measure.

Manné recalls a minor strike to his rib area that, while bearable at the time, left him barely able to move a few days later. “It’s amazing, it just takes away your spirit to fight… it makes you feel nauseated inside, and you don’t want to continue. I wish I’d found this years ago,” admits Manné.

“I’ve been around, everywhere, and I haven’t found anyone who can do what he does,” says Jones. “The closest I’ve seen is [on a seminar video] – this guy from Russia, from Systema [Mikhail Ryabko], who can hold down a huge wrestler with one finger.”

But what is it exactly that the Zen Do Kai men have found? What is it that McRae’s doing that they hadn’t discovered in over 40 years of training and applying their skills, some of which they’ve travelled the globe to learn?

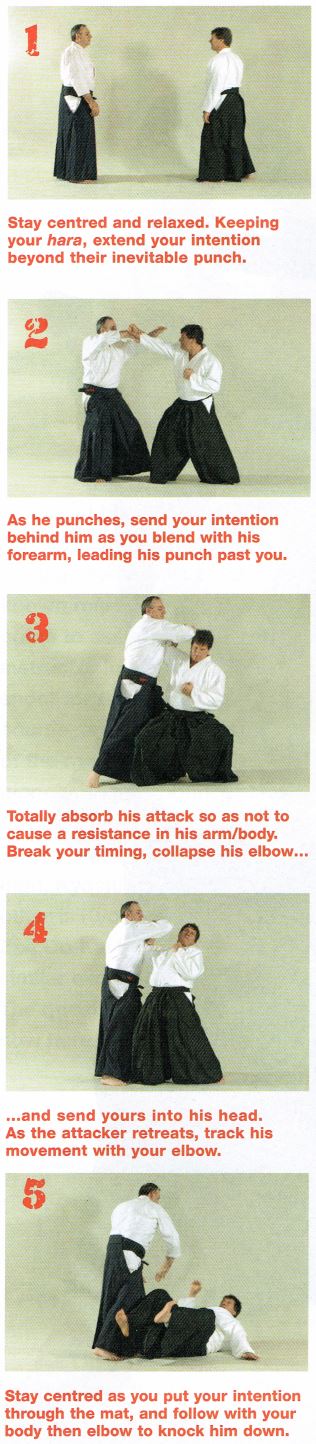

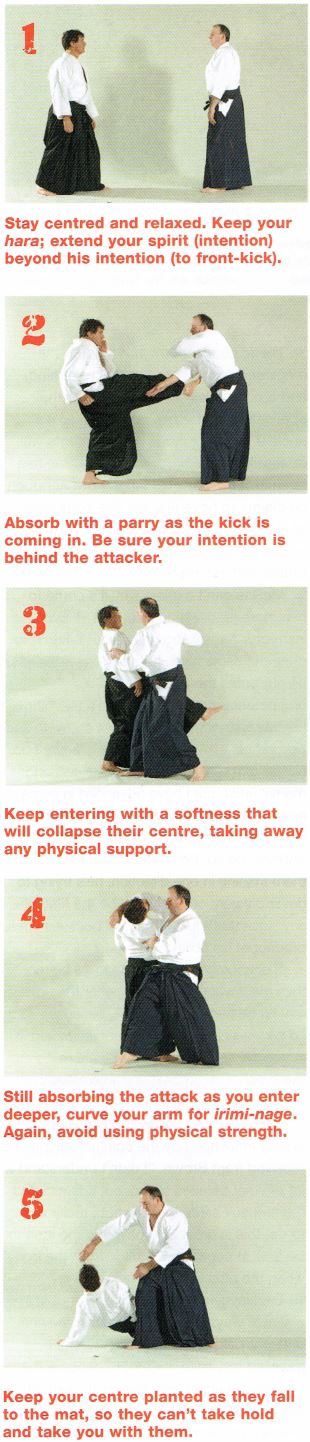

McRae knows it’s difficult to put into words – not so to feel – but does his best: “I fuse their ki – which is the person’s spiritual intention, which means their action to attack with their physical presence – with my intention. I lead it so that it separates from their physical body. Their spiritual intention and their physical self separate so that I don’t have to deal with their physical body so much.”

In essence, as I understand it, he is controlling my body by first taking charge of my preceding intention to push, pull or grab.

“When they attack, their mind and their body – their intention of the attack and their physical body – is together. What I specialise in is, I remove their intention from their physical self at that moment. I lead their intention so that their physical isn’t attacking me along with their intention,“ McRae explains.

Warming to the topic, he grabs Peter’s wrist and points to it (now, concentrate): “My mind is there, so, I have to take…” He rethinks his position. “If it’s reversed around, like if he’s grabbed me” – they reverse, so Peter now has hold of McRae – “his mind is there” – he points to Peter’s grip. “So, if I try to get out of that, his mind and my mind are there… so I’ve got to lead his intention so that I can get out of there; his mind has to be led so that his mind, with his physical, is not holding me. How you translate that I don’t know… You’ve got to feel it to experience it, really.”

I would have to agree. But having done so, I can appreciate the round-about explanation – it’s not as effusive as it might sound. The name McRae has given to his method, ki fusion, gives a little more insight. A definition for ki, the Japanese term for what the Chinese call chi, is elusive, but is variously described as a life-force or universal energy that runs through our bodies. McRae’s description is as revealing as any I’ve heard:

“It’s not mysterious. It’s not mystical. Everyone’s got it; it’s our life energy. So what we’re trying to do is be like an antenna that sucks that energy in from the universe that’s been bombarded since its creation. The energy has got to be renewed constantly, so that we’re like an aerial. The energy comes in and we’re the vehicle that uses that energy. Then we have to replenish it. So, what we’ve got to learn to do, after years of training, is to be able to bring that energy in and release it out as we’re training so that we don’t get so tired, because it’s not a physically generated action.”

As for ki fusion, McRae says, “I thought of the name probably back in 1988, to try to describe what I was doing. I trained and viewed aikido a little bit different to the average aikido person … I thought, I’m fusing ki together, so, ki fusion. It’s about your ki and his [the opponent’s] becoming one.”

As for ki fusion, McRae says, “I thought of the name probably back in 1988, to try to describe what I was doing. I trained and viewed aikido a little bit different to the average aikido person … I thought, I’m fusing ki together, so, ki fusion. It’s about your ki and his [the opponent’s] becoming one.”

These concepts might verge on the magical, especially to the Western mind, and are not easily understood, nor their application learned – especially as it’s unclear which of those achievements will, or should, come first. Indeed, McRae has been at it for some 25 years now, although he claims to have first felt this command of ki as a 1st Kyu (Brown-belt). From then on, he put all his focus into cultivating it further within himself.

McRae can’t explain why it’s come to him more readily than to others – even his instructor Sensei Brown has not taken it to quite the same level, he says. Nevertheless, he attributes the awakening of his understanding to David Brown’s teaching.

“My instructor gave me that ability, to see beyond his thinking, and in some areas I do. Not all of them. David is still a devastating martial artist, but I have advanced in some areas a little bit beyond his thinking, but that’s only natural because he gave me the ability to do so. He can’t cover it all. I’m out there training in one direction; he’s trying to cover different ones … He’d be the first to say, ‘look that’s just fantastic,’ because I’m a product of his ability.”

“I encourage my students to be better than me. I want them to be better than me. I’d be sad if they weren’t, because I’d be wasting my time. I have no interested in striving to be always better than them like, ‘yeah, I’m the best.’ I’m interested in encouraging my students to see even beyond me.”

McRae’s own understanding was greatly influenced from the countless spiritual lessons discussed from Brown at work. “I couldn’t absorb a lot of what he was trying to explain back then but it really fascinated me so I said, this is what I really want to do, this is great”. “He also explained his idea to separate the mind from the body if attacked.”

Lindsay learned the true power of ki in a similar way, though he took a somewhat different path in getting there. First, he travelled to Osaka, Japan, to become the first foreign uchi-deshi (live-in student) at the Suita dojo, home to his instructor’s teacher, the Grandmaster Seiseki Abe, 10th Dan, and his chief assistant Kinoshita Sensei. He explains that ki and its attendant concepts were not so much explained at the Suita dojo. Instead, an understanding of such ideas was sought through breathing techniques, coupled with the spiritual pursuits of Shinto prayer, called kotadama (‘sound-spirit’) and misogi, the rituals for purifying the spirit, which involved splash oneself with cold water, and other quiet pursuits such as calligraphy.

As a body builder, Lindsay had spent years building an impenetrable wall of muscle; contracting, flexing, bulking up … not things normally associated with suppleness of body and spirit. Although the prayer and training had begun to quieten his mind, the real breakthrough in his understanding of aiki concepts and manipulation of ki came when he fell extremely ill and lost 20 kilograms of body weight in six weeks. The mystery illness enveloped him after injuring his back wielding a heavy boken (wooden sword).

“I’d go in the morning and grab the big boken that Kinoshita Sensei had made out of a tree branch, because I was still full of ego and wanted to keep the arms buffed. So before all the students have got their Japanese shoes on, I’m going up and down the dojo [swinging the boken] and my back went,” Lindsay remembers. “Then all of a sudden I got a bloated stomach and boom. I was in so much pain, I used to lay on my back after class and nearly cry. I stayed there for three months, Abe Sensei took me to two hospitals they couldn’t find out what was wrong. My body shut down and that’s the test that I went through. Because I could not use one bit of strength, I had to find another way, and learn to use ki. Then Abe Sensei said, ‘Now you understand real aikido’.”

Lindsay and McRae met in 1994, after Lindsay appeared on the cover of Blitz with a story about his training under Steven Seagal Sensei at his (former) Tenshin dojo in Los Angeles. McRae, eager for knowledge, went to meet him. They kept in contact, on and off, until 2006, when McRae asked to join him in building his organisation.

Like Lindsay, McRae wasn’t always a master of his ki. He had a hard exterior to break down before it could really flow. Discovering – let alone mastering – something like ki fusion was far from his mind when he and an even burlier mate sauntered onto the tatami mats with Sensei David Brown for the first time.

“Growing up I was a bit aggressive. I lost my father when I was 11, and that made me very angry. I couldn’t understand why he left me, if you know what I mean? I had met David Brown a couple of years after I lost my father and he became like a father figure … He sort of helped me to get on the straight and narrow,” says McRae.

When he became Brown’s apprentice, McRae never knew his boss taught aikido – he didn’t even know what it was. But he remembers clearly when he first saw Brown take a class, at Kyoshi Tino Cebrano’s Goju karate dojo in Balwyn back in 1977. Already a senior rank in Australian Aiki-Kai, Brown invited his young charge along after McRae’s curiosity was aroused by his collection of aikido books.

“So I showed up with my best friend, who was six-foot-seven, built like a tank and strong as an ox. My friend Stewart was giggling and we were both trying not to laugh, because it didn’t even look like a martial art at the time. I’m thinking what’s he doing, it was like dancing or something. I said, ‘Thanks Dave! I’ll see you at work tomorrow’,” McRae remembers. “And he says, ‘Come here, you’re not getting out of it that easy – shoes off! Both of you!’ Then he starts showing me some of the ki stuff. He said, ‘throw a punch’, and I threw a punch and I’m down on the ground.’ He said, ‘lift me off the ground.’ I couldn’t. I knew I was physically stronger than him, so I got Stewart to do it, and he couldn’t lift him either. He put his fingers together – I couldn’t pull his fingers apart with two hands. I said, ‘What’s going on here?’ I couldn’t figure it out. And he said, ‘Well this is ki – your internal energy. He says, ‘I’ll teach you how to do all this.’ I said, ‘right, I’m starting. I’ll start tomorrow’.”

Though what he craved was mastery of such powerful technique, what he eventually discovered, he says, was love. Although like Manné, he also discovered that love hurts. It was a realisation won through hard training, with the contradiction that all the time he was learning to be soft, in both his technique and his approach to people. However, he’s quick to point out that softness in aikido is not as we know it. “Everyone has this ability of being able to be relaxed and being able not to clash with the other person’s strength, but it’s not softness in the normal sense, it’s softness with an enormous amount of power behind it.

“The way we fight with one another, occasionally we do one little thing wrong, we can hurt the person and could put them in a wheelchair, no problem… There is a destructive side to aikido, but we really don’t want to go there. And in my personal opinion, I want to learn and teach aikido where it’s that powerful but it’s so soft that you can’t actually feel what’s hit you.”

That said, McRae is quick to say that hitting anyone is low on the list of aikido’s aims, softly or otherwise. Applying the principles of aikido is about much more than technique – which is where the love concept comes in.

“You can’t beat everybody up, you can’t think that you can. But what you can do is train yourself to become a better person and when you’re a genuine better person, that rubs off onto other people. People only want to fight you when you’re a threat, if you’re not a threat then people don’t want to fight you,” McRae explains, getting more philosophical. “Everyone wants to be respected and everyone wants to be appreciated, so, instead of trying to think I’m better than someone else, I want to appreciate other people – and that’s in the training. That’s the true teachings within the aikido that I understand. When you don’t look at people as threatening, you become non-threatening. And it’s only when you’re scared of the other person that you have to have a facade of toughness and muscle power and I don’t want to go down that path, I don’t have that interest.”

McRae even demonstrates to me a technique he uses, which he describes as “diminishing [his] skeleton”. It certainly helps explain why I was a little confused when he met me at his front gate, not looking as much like the large, burly man I’d seen in photos.

“When I say that I diminish my skeleton, I don’t do it in a stooped way, I do it in straight form. So I compress it downwards and become smaller as I approach you. It shows a non-confronting attitude to the other person. That person feels no threat whatsoever and when they feel no threat, they open right up to you. And they think, ‘well there’s no threat, I’m not interested in fighting this person’.”

So this is the stuff of warrior arts – love, compassion and selectively diminutive stature? Lindsay believes so, despite having an irimi-nage (neck-throw) powerful enough that it “could knock your head clean off!” as McRae puts it.

“Abe Sensei’s so enlightened that when you’re around him he takes the fight right out of you. He says, ‘You can’t resist that which does not exist’. He doesn’t give you any aggression… Ultimately all he gives you is love and I tell you, hardcore karate guys in Japan – I won’t mention any names – that have been with him and on the way home, back to the train station, they’re crying, because Abe Sensei was giving them so much love that it took everything out of them. And it’s very confronting – love’s very confronting. That’s what you want to be like, but that can take a long, long time.”

But, when you’re driving a prestige car, a farther destination just makes for a more enjoyable journey. Blitz (2007).